Let me be upfront: I was there on August 28, 1965, but I remember little about it. What I do remember is that it was, and still is, the strangest concert I’ve ever attended.

So, I wondered, Is it possible to recall a vague memory that happened 60 years ago and make sense of it today? Could research reconnect sleeping neurons and help me understand what really happened on that one strange night?

Watching A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic with a memorable performance by Timothée Chalamet, recently triggered that long dormant memory. The Forest Hills concert was Dylan’s next public appearance after being booed at Newport just a month earlier for daring to plug in and play electric. Up until then, he’d been the lone troubadour: acoustic guitar, harmonica, and words that shook a generation. But the winds of change were already blowing.

For many, Dylan’s transformation felt like betrayal. For me, that night was simply bewildering. I couldn’t make sense of what I saw — but six decades later, I crave to.

The Times They are a-Changin’

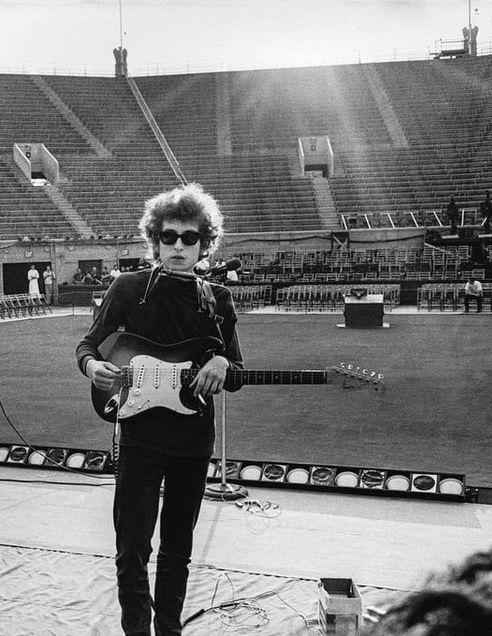

We sat in Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in Queens, New York among 15,000 fans filling the horseshoe-shaped arena built for tennis, not rock. Forest Hills was an ideal outdoor venue for a large audience drawn from the New York metropolitan area, including the important Greenwich Village folk scene. Acts like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Frank Sinatra had previously played there. In fact, Dylan had played there just a year before, appearing with Joan Baez.

At just 24, Dylan had already become the reluctant “spokesman of a generation.” His lyrics carried rebellion and poetry in equal measure — a mix of Woody Guthrie grit and James Dean defiance. America in 1965 gave him plenty to sing about: war, inequality, and political unrest.

Many think of Dylan as a protest activist. But he was never a joiner — he gave voice to movements without belonging to them. His songs were protest anthems, even when he refused the label “protest singer.”

“I’m not writing for any movement. I just write what I see.”

– Bob Dylan at interview with Studs Turkel (1963)

Yet the times and the sound were changing. Rock music, born in the 1950s, had exploded. By 1965, Dylan sensed it was time to evolve. He began to push both his music and his audience toward a new hybrid of protest and power, folk-rock.

Like a Rolling Stone

In March of 1965, Dylan released his fifth album Bringing It All Back Home. One side is solo acoustic; the other electric backed by a studio band. The album cover design and music were a clear sign to his fans that he was resetting his style.

Then came the single Like a Rolling Stone (listen) (lyrics) which was recorded in June and released July 20, 1965 before appearing on his next album. This was five days before his notorious appearance at the Newport Folk Festival (July 25, 1965).

The song quickly made the top radio charts even though it had an angry protest message, full use of electronic instruments, and was over six minutes long instead of the industry-standard three minutes. It violated all those norms while creating a popular bridge between folk lyrics and the infectious sound of rock music.

“The first time that I heard Bob Dylan I was in the car with my mother, and we were listening to, I think, maybe WMCA, and on came that snare shot that sounded like somebody kicked open the door to your mind, from ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’ And my mother, who was – she was no stiff with rock and roll, she liked the music, she listened – she sat there for a minute, she looked at me, and she said, ‘That guy can’t sing.’ But I knew she was wrong. I sat there, I didn’t say nothin’, but I knew that I was listening to the toughest voice that I had ever heard.”

– Bruce Springsteen

The afternoon before the concert my friend Mike Kennedy called to say he had extra tickets, thanks to his older brother Tom, a Columbia student who was tuned into the changing scene. Mike and I were just 17 years old, Jersey high-schoolers trying to be cool. We’d heard some Dylan, but didn’t yet get Dylan.

We definitely weren’t ready for what we were about to witness.

With No Direction Home

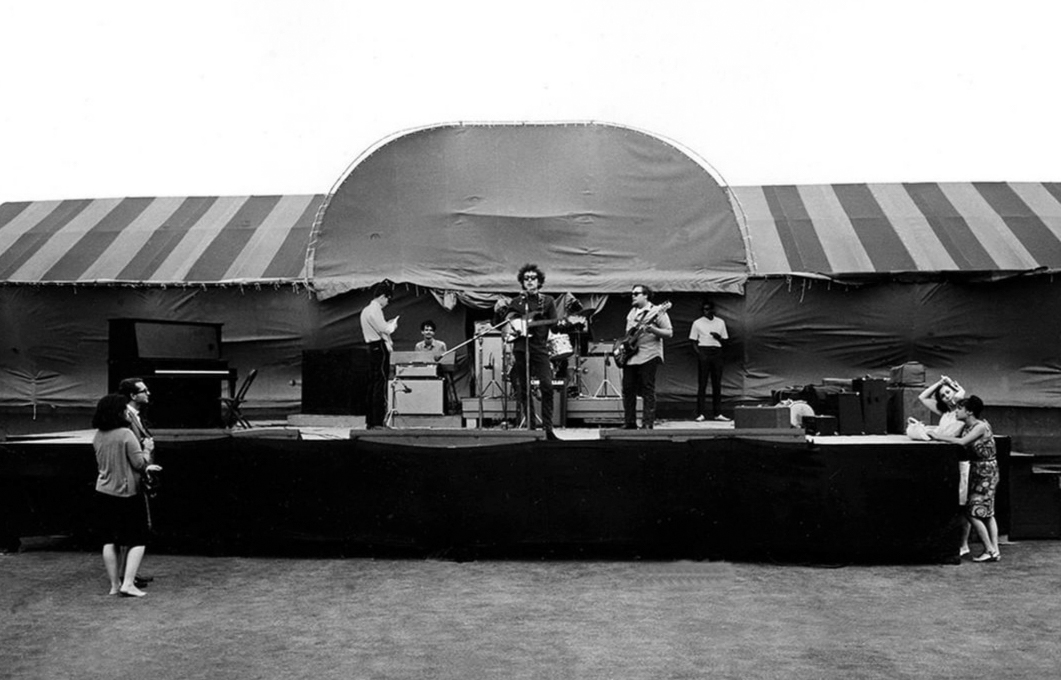

Sound check and rehearsal pre-show at Forest Hills.

Dylan wanted the sound just right after technical problems at Newport. He knew this would be big raucous event and prepared the band or the mayhem that would follow.

On this unusual windy and cool August night, temperatures dropped from the 80s to the 50s and brought gusty winds. It was an omen of what was to come. We were sitting on bench seats in a steep upper deck of a very dark stadium. Everyone was focused on a single miasma of brilliant light shining on the platform stage where Dylan and his band would perform. You could immediately feel the nervous energy of the buzzing crowd in anticipation of Dylan’s appearance.

Everyone wondered: would Dylan go electric again, like at Newport?

He would — but only halfway. The plan: an acoustic set first; then an electric one.

But the tension was already in the air.

He Really Wasn’t Where Its At

The concert opened oddly with “Murray the K” Kaufman, a popular Top-40 DJ, as emcee. Folk purists booed loudly. To them, Murray symbolized the commercial rock world they despised. It was a taste of things to come.

You Say You Never Compromise

The first half of the concert went smoothly. It was the acoustic set which everyone recognized and seemed to enjoy. That is to say Dylan performed solo with guitar and harmonica in his usual style. The 45-minute set including She Belongs to Me, To Ramona, Gates of Eden, Love Minus Zero/No Limit, Desolation Row, It’s All Over Now and closed with Mr. Tambourine Man. This set featured the public debut of the ten-minute long “Desolation Row,” which went over very well with the entire crowd who appreciated its clever caustic lyrics.

To Hang On Your Own

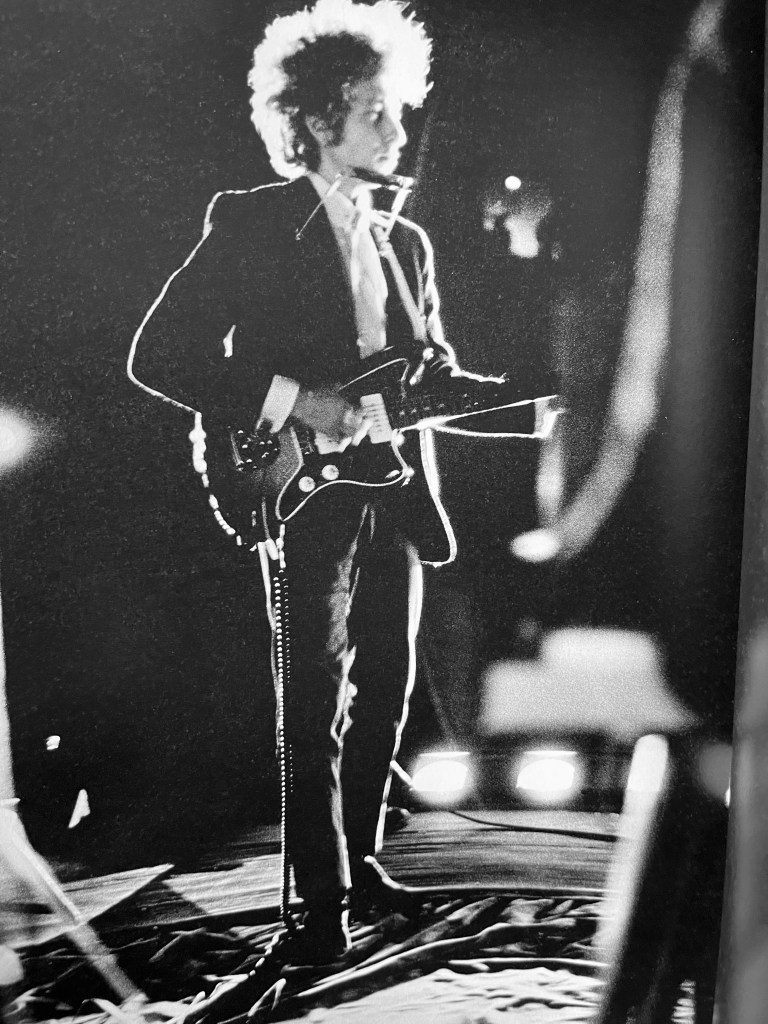

After a fifteen-minute break, everyone knew something big was coming. Dylan appeared accompanied by a band of four relatively unknown musicians at the time – Robbie Robertson (guitar), Levon Helm (drums), Al Kooper (organ) and Harvey Brooks (bass). Over the years they would create their own history in the world of rock and roll.

They launched into Tombstone Blues. The stadium erupted — not with joy, but outrage.

“Due to the stage lighting, we couldn’t see the audience – only the deep green lawn in front of us. Since Dylan had gone electric a few weeks earlier at Newport, uncertainty about what would happen here – his first live performance since Newport – was running high. The audience was self-righteously hostile and they didn’t hide it.“

– Harvey Brooks (bass guitarist)

Boos, shouts, insults. “Scumbag!” someone yelled. Dylan shot back, “Aw, come on now.” That was followed by a chorus of “We want Dylan.”

Dylan had already anticipated the negative reaction. According to Harvey Brooks Dylan warned the band, “I don’t know what it will be like out there. It’s going to be some kind of carnival, and I want you to all know that up front. So go out there and keep playing no matter how weird it gets!”

And weird it got. The crowd seemed to quiet a bit after a few songs. But as the set went on the audience grew restless. Half-way through the set, fans ran across the grass toward the stage only to be tackled by security guards. Al Kooper’s organ was knocked over and Levon Helm had to hold off a couple protesters charging his drum set. Objects were thrown at the stage. Still, Bob and the band played on!

The electric set included Tombstone Blues, I Don’t Believe You, From A Buick 6, Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues, Maggie’s Farm, It Ain’t Me Babe, Ballad Of A Thin Man, and Like A Rolling Stone. When he got to Ballad of A Thin Man, Bob played the intro over and over again until the audience quieted down. The concert ended with Like a Rolling Stone and a dozen teens rushing the stage amid the sound of cheers, jeers, and a sing-along! When the song ended Dylan said, “Thank you very much,” and walked off the stage without an encore.

The reaction at this concert, and others that followed for over a year, often resembled what started in Newport as a revolt of his fans. That second set clearly split the audience into fans and enemies of the new Dylan.

I didn’t understand the reasoning and hostility but realized that it must have been important enough to have Dylan rebel against his own musical style. I can’t say I enjoyed the concert as much as watching the emotions in the crowd.

“The electric band and the high voltage vocalizing raised the level of Mr. Dylan’s performance from the intimate introspective vein of the first half to a shouting, crackling intensity.“

Robert Shelton, NY Times, August 30, 1965

Dylan had played in a folk style for years, yet he appreciated the new rock sound. In fact, Dylan once said, “I just got tired of playing guitar by myself.” He felt he needed to draw other instruments and musicians into the process.

And Now You’re Gonna Have to Get Used to It

Other singers and rock groups such as the Byrds, Sonny and Cher, Barry McGuire, and the Rolling Stones either copied Dylan or carried their own anti-establishment and free-spirited messages in their songs. Dylan helped move the counter-culture movement that was already reaching a broader popular audience. Pure folk music continued with Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and groups like Peter, Paul and Mary, and the Mamas and Papas, but would lose much of its momentum to a changing culture and sound. Music became more political, poetic, and electric, mirroring the headlines.

How Does It Feel?

One interesting observation of the concert was that Dylan, while upset at the performance in Newport, was exhilarated by the crowd at Forest Hills. According to band members Kooper and Brooks at a post-concert party, Dylan bounded across the room and hugged both of us. “It was fantastic, a real carnival.” He began to appreciate that fans were reacting to his music. He said to one woman who was said to not have enjoyed the set, “You should have booed me. You should have reacted. That’s what my music is all about.”

“I thought it was great, I really did. If I said anything else I’d be a liar.”

– Bob Dylan on the Forest Hills Concert – Interview by Nora Ephron & Susan Edmiston, summer 1965

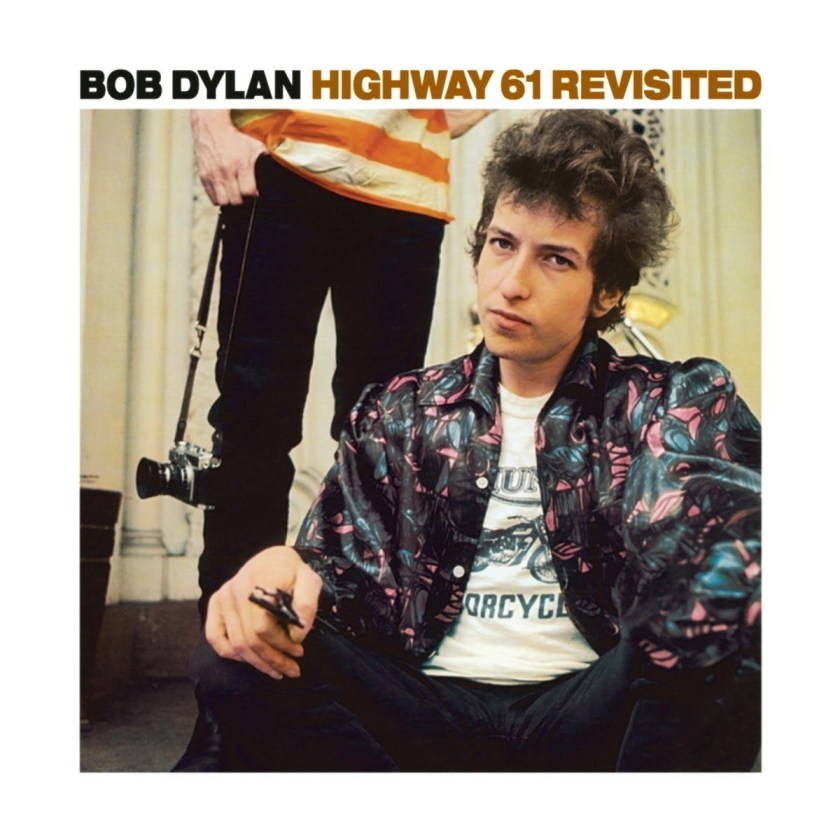

Two days after the Forest Hills concert, Dylan released Highway 61 Revisited, his first full rock album. Its title was a play on U.S. Highway 61, known as the “Blues Highway.” It contained his hit single, Like a Rolling Stone, and was a mixture of songs that tied folk-blues to rock, some of which he introduced at Forest Hills. The album was a success and is considered among the greatest albums of all time.

Dylan went on a worldwide concert tour for the next year with his own band playing a similar format of half folk – half rock format, and fan anger continued. There would be no turning back.

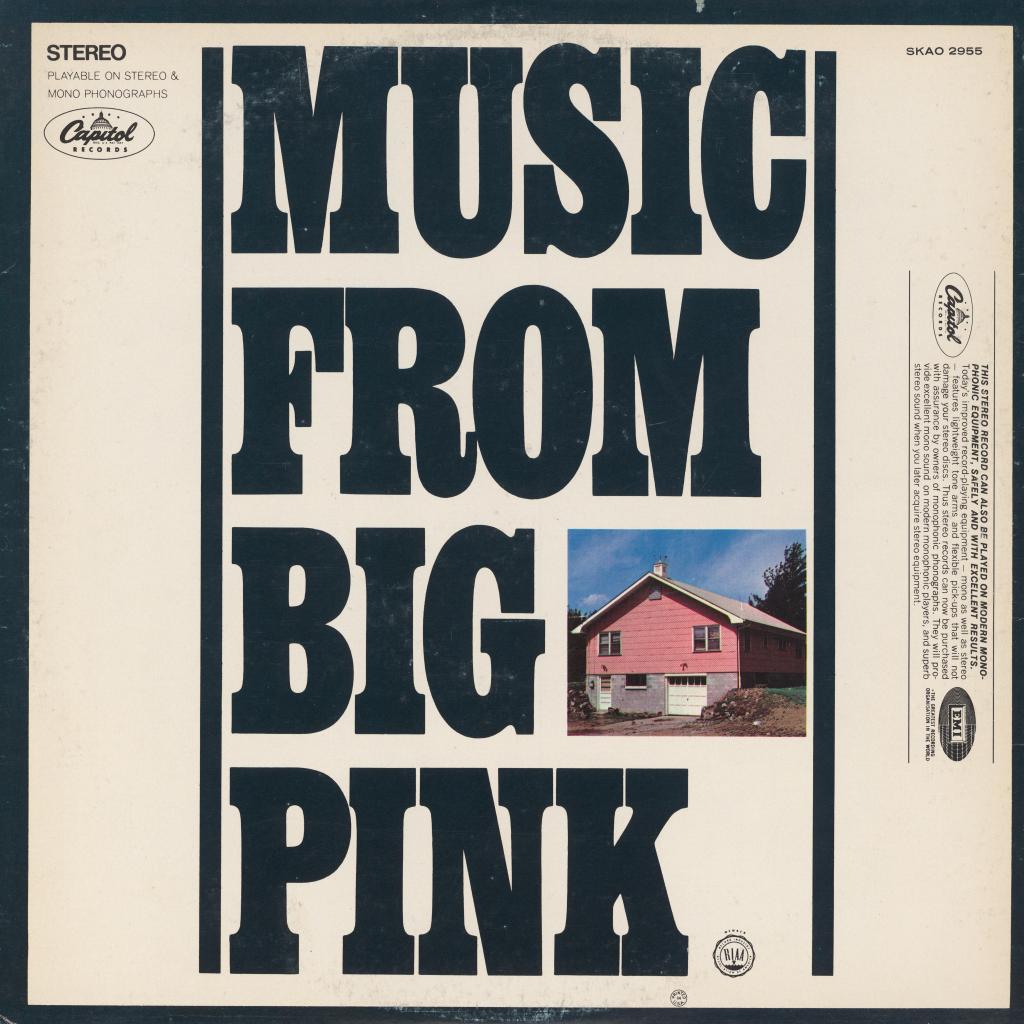

Impressed by Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm at Forest Hills, Dylan soon brought in their bandmates — Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, and Richard Manuel — formerly of Ronnie Hawkins’ group, Levon and The Hawks. Together they would tour the world, then retreat to Woodstock to become The Band and record Music From Big Pink — one of the era’s masterpieces..

Epilogue

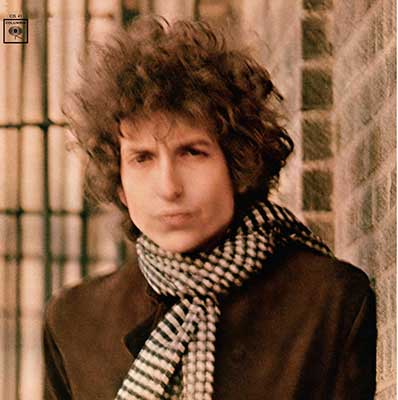

Dylan’s folk-electric rock period would end abruptly in mid-year 1966 after he had released his seventh album Blonde on Blonde (June 1966), a highly creative double album. Some say this was maybe his most creative period with hits like “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” “I Want You,” “Just Like a Woman,” and “Visions of Johanna“.

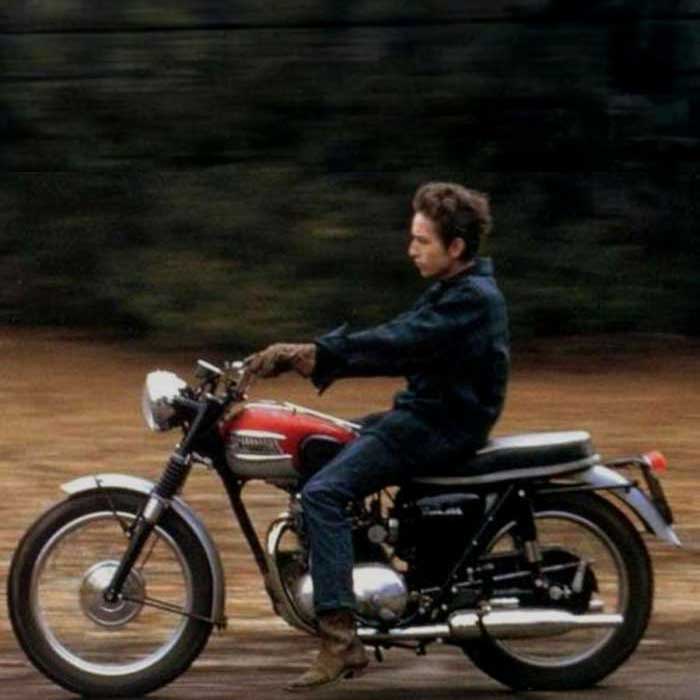

On July 29, 1966 he was seriously hurt in a motorcycle accident near his home in Woodstock, N.Y. Rumors surrounded him. Despite reports that he had serious neck vertebrate injuries, no hospital records were ever discovered. Some speculated that he had enough of the tour and wanted to retreat from the fame. He cancelled all tour dates and retreated out of public attention for the next year.

During that year off, he began to collaborate with his bandmates, formerly know as “The Hawks.” Meanwhile, they would release their own famous Music From Big Pink album created at nearby Saugerties. That album would be hailed as a masterpiece and launch their successful career as “The Band.”

During his recuperation Dylan would work on music that would evolve into his eighth album, John Wesley Harding (December 27, 1967)- which had a distinct country and blues sound and included a new big hit I’ll be Your Baby Tonight. Once again, proving his musical style was always changing.

His style and audience had changed. In fact, throughout his long career to this day, he would constantly change his music, the way it is played, and his interests. Change has always been his one reliable constant.

Afterword

That night in Forest Hills was my first Dylan concert. I’ve seen him a few times since, always curious what he’ll sound like next. My search for reviews and recollections led me into a tangle of lore — Murray the K, Al Kooper, Harvey Brooks, Albert Grossman, Daniel Kramer, Tony Mart, and “The Band.”

No video exists of that concert; only a rough bootleg recording survives. But after revisiting it through memory and research, I realize how lucky I was — to have been there when music, and culture itself, shifted gears.

I may be too old now to recall every detail, but not too old to appreciate it anew.

Long live Dylan — and the memories he still manufactures.

Bonus Tracks

Harvey Brooks Remembers

Harvey Brooks played bass during that electric second set at the Forest Hills. He vividly remembers how strange the night was. Brooks was a renown studio bass player and played on the Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde and Blonde albums. He was asked by Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman to play on tour for two concerts one at Forest Hills and the other the Hollywood Bowl. He would be replaced by Rick Danko of The Hawks (which would become The Band) for the rest of Dylan’s worldwide tour.

Al Kooper On His Most Famous Organ Riff

Studio musician Al Kooper played organ at Forest Hills behind Dylan. But the story behind how he got involved is an interesting combination of luck and one brilliant organ riff when recording Like a Rolling Stone . Kooper went on to a successful career as songwriter, record producer, and musician. He played behind many famous musical recordings and founded the group Blood, Sweat and Tears. Kooper was replaced in Dylan’s band after two concerts by Garth Hudson of The Hawks (which would become The Band).

Daniel Kramer on Photographing Bob Dylan

On August 27, 1964, the young aspiring photographer Daniel Kramer made a pilgrimage to Woodstock, NY to propose to act as personal photographer for Bob Dylan. Dylan agreed and Kramer went on to produce some of the most iconic and beautiful images of Dylan in his heyday – for exactly one year and a day. Those included album covers, time with friends and concerts such as Forest Hills. Here he shares some of his thoughts on that one-year assignment that brought him fame and added to Dylan’s legend.

Kramer’s opus “Bob Dylan: A Year and a Day” is a great story and source of beautiful images of Dylan in his heyday 1964-1965. This should be on the book shelf of every true Dylan fan. More on Kramer’s work.

Sources

Books

- Elijah Wald, Dylan Goes Electric: Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night That Split the Sixties. Harper Collins, NY, 2015

- Robbie Robertson, Testimony, Penguin Random House, NY, 2016

- Levon Helm, This Wheel’s On Fire, William Morrow and Company, NY, 1993

- Daniel Kramer, Bob Dylan: A Year and A Day, Taschen, Cologne, Germany, https://www.taschen.com/en/books/music/44841/daniel-kramer-bob-dylan-a-year-and-a-day/

Articles

- Caryn Rose, Here’s a Look Back at Bob Dylan’s Best NYC Concerts, The Village Voice, November 25, 2015

https://www.villagevoice.com/heres-a-look-back-at-bob-dylans-best-nyc-concerts/ - Hilary Hughes, 50 Years After Dylan Played Forest Hills, Al Kooper Recalls 1965’s Electric Summer, The Village Voice, August 25, 2015

https://www.villagevoice.com/50-years-after-dylan-played-forest-hills-al-kooper-recalls-1965s-electric-summer - Stuart Mitchner, Robbie Robertson Gives It “All His Might” in “Testimony, Town Topics, Princeton NJ

https://www.towntopics.com/2023/08/23/robbie-robertson-gives-it-all-his-might-in-testimony/ - Forest Hills August 28, 1965, PunkHart Productions, Provides a good online summary of the concert and its importance for Dylan and fans.

https://www.punkhart.com/dylan/tapes/65-aug28.html - Bob Dylan Press Conference, KQED Studios, San Francisco, CA, December 3rd, 1965

Transcript of a long interview with Dylan during the folk-electric tour with some insight on his music and showing how he always befuddles interviewers.

https://dylanstubs.com/extras/1965.pdf - Nora Ephron & Susan Edmiston, Don’t Look Back — Bob Dylan Speaks, New York Herald Tribune Sunday Magazine, New York, June 6, 1965

Transcript of a long interview in the transition period to electric. Famous for Dylan responding to a question if he was a poet, “Oh, I think of myself more as a song and dance man.”

https://www.interferenza.net/bcs/interw/65-aug.htm - Joker and the Thief Newsletter, Bob Dylan at Forest Hills, 40 Years Later,

https://peterstonebrownarchives.substack.com/p/bob-dylan-at-forest-hills-40-years - Thomas Meehan, Public Writer No, 1?, New York Times, December 12, 1965

Meehand discusses the question of Dylan being a true poet for the generation. - Robert Shelton, Dylan Conquers Unruly Audience, New York Times, August 30, 1965

Shelton offers a positive review of the Forest Hills concert in spite of the negative reactions. - Dave Moberg, The Folk and the Rock, Newsweek Magazine, September 20, 1963

Discussion of the new folk-rock movement created by Dylan - Harvey Brooks, Forest Hills and the Hollywood Bowl: The Days after Bob Dylan Went Electric. The Times of Israel, Aug 28, 2015

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/forest-hills-and-the-hollywood-bowl-the-days-after-bob-dylan-went-electric/

A great article by Harvey Brooks who was playing bass that night in Forest Hills.

Media

Audio Recordings

Bob Dylan – The Forest Hills Concert (Swingin’ Pig Remaster) [Aug 28, 1965]

This is the only audio copy of the original concert. It’s a rough unprofessional recording but covers most of the concert.

Click here to listen

Documentaries

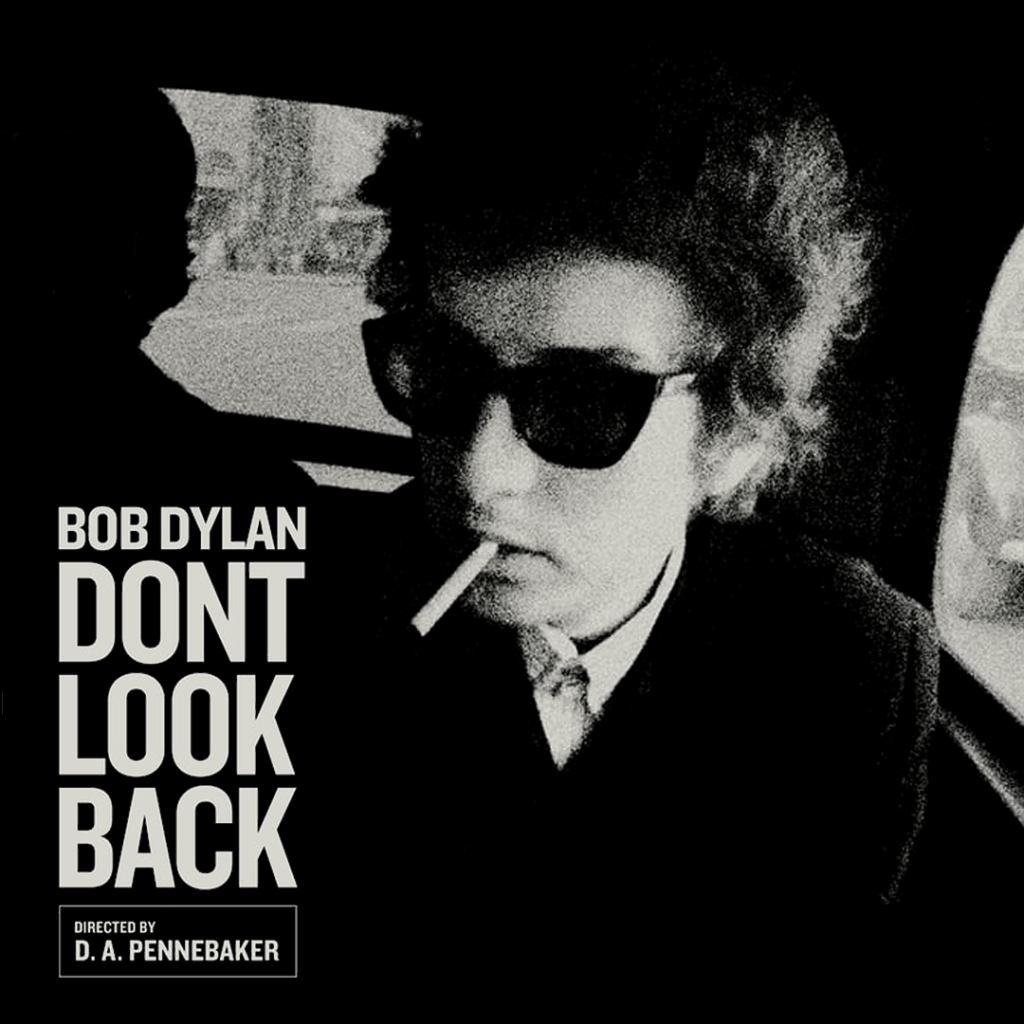

Dont Look Back, 1967

Director: D. A. Pennebaker

The definitive Dylan documentary — raw, handheld, and intimate. Dylan’s 1965 U.K tour. Captures him just as he’s leaving folk behind for rock. Led to the behind-the-scenes documentary format in film.

Watch options.

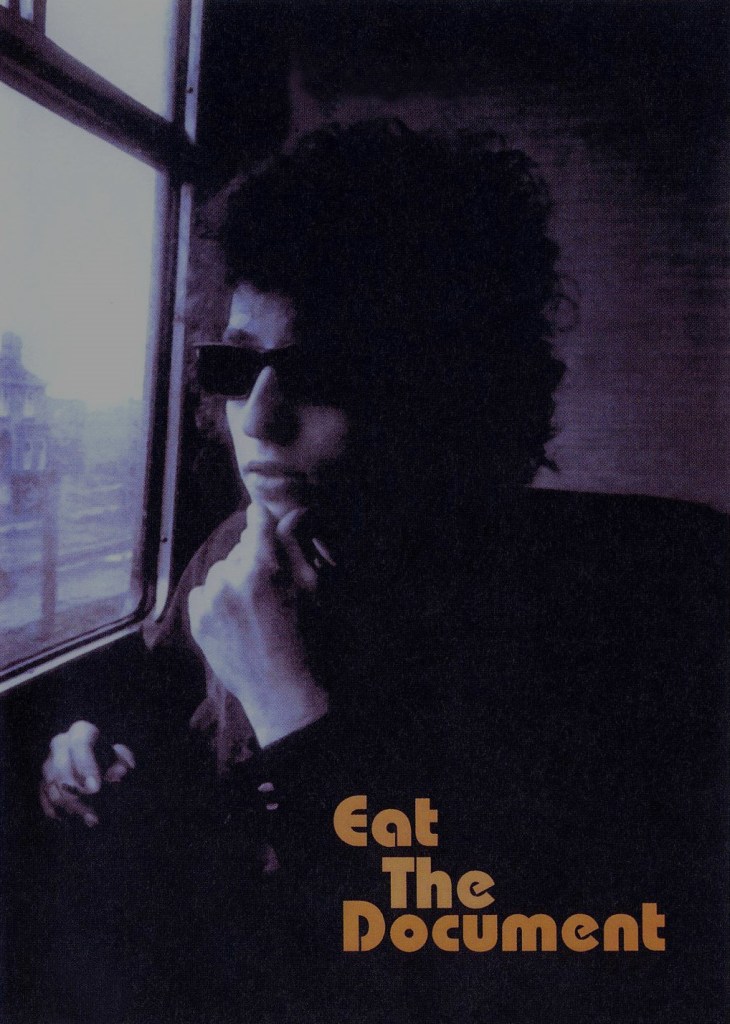

Eat the Document, 1972

Directed by: Bob Dylan & D. A. Pennebaker

Dylan’s 1966 European tour with The Hawks (later The Band) This film shows Dylan’s onstage electricity and offstage exhaustion during his chaotic “electric” phase.

Watch options.

The Last Waltz, 1978

Director: Martin Scorsese

The Band’s final concert and one of rock’s greatest films. Dylan appears near the end — his tribute to having been backed up by these performers on his 1966 tour. Other famous musicians including Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and Eric Clapton join in.

Watch options.

No Direction Home, 2005

Director: Martin Scorsese

Film produced with Dylan’s cooperation focusing on Dylan’s early years, 1961–1966. Includes archival footage from Newport Folk Festival and 1966 World Tour showing his evolution from folk hero to rock revolutionary.

Watch options.