Upsala College Seal

Vincit omnia veritas

(truth conquers all)

As time passes, inevitably we lose an intimate connection with the past. People and places that were once essential to our lives become distant ephemeral memories. The truth is nothing is the same as it once was. But every so often it’s worth stopping and asking why. Why did something change so drastically? Why did an esteemed educational institution utterly fail when it once seemed so competent and permanent?

I graduated Upsala College in East Orange, N.J. in 1970 with a B.A. in Economics. Twenty-five years later it was no more. Over that period, the school would change from one of the top three New Jersey private colleges to the bottom triggered by low enrollment, sliding academic standards, unpaid bills and blatant mismanagement. The press reported that the closing was due to its inability to pay off its $12.5 million debt. But, that was only the obvious reason to close. There was much more that had gone wrong.

Its last commencement on May 14, 1995 (Mother’s Day) was a funeral of sorts. Upsala closed its doors and soon abandoned the 45-acre hilltop campus. Along with celebration and fond memories, there were the physical and mental scars created for all those that learned, socialized and lived around the campus area.

I could never explain to anyone exactly why the death of my 102-year old college happened and I still wonder about its story. Today, fewer and fewer people remember the school. I became obsessed with Upsala’s story and began to explore it again looking for answers. Here’s what I learned about “what” happened. There’s still more yet to tell as to “why” it happened.

My College No More

Upsala maintained its 45-acre city-campus there for 71 years after relocating from Kenilworth in 1924 and Brooklyn in 1897, where it was founded. A Lutheran Synod ministry created the school in 1893 to educate Swedish immigrants and named it in honor of the great Swedish Uppsala University. It was known over the years as a quality liberal arts college comparable to nearby Drew, Fairleigh Dickinsen, Wagner, Muhlenberg and other private colleges. Its connection to the Lutheran church and religious learning faded over time, long before I attended.

For the first half of the 20th century, East Orange, a smaller city on its own, was the wealthier outgrowth of a migration from the larger commercial hubs of Newark, Elizabeth and New York. Only a few miles from the great metropolis, it had superior highway and rail access with a spacious natural beauty. It had the feel of a suburb with the commercial benefits of a city. In other words, it seemed a perfect place to operate a well-respected college.

In 1968, I transferred to Upsala with an A.A. degree from Union County College, a two-year community college. Without enough family financial resources, the choice was simple – commute to UCC and then Upsala while working part-time and benefitting from a small NJ State scholarship. I was able to attend UCC paying cash, while taking a small loan to cover my last two years of tuition at Upsala. A few years later, I earned an MBA from Rutgers with the help of tuition assistance by my employer. In summary, I was relatively debt-free in my mid-twenties with an advanced degree, a business career and a marriage. There was little reason to look back and much to look forward to.

While my time at Upsala was rewarding and productive, it was hardly the “full” college experience, being a “commuter” student. There was little reason to connect again with Upsala except when I needed a transcript. Occasionally, I’d hear or read about their sports teams, which were usually fairly good and competitive. I don’t recall receiving requests for alumni donations or campaigns. I never knew about the school’s financial problems or thought much about the changing demographics. But working in the greater Newark area, it was obvious that the whole urban landscape was deteriorating. Over the years, the word came from the press and friends that Upsala had fought for years to remain open but eventually gave up and closed.

News of its demise was something like hearing a distant uncle had died at an early age. It seemed like my two brief years at the school should not justify much sympathy. The problems that closed the school were not at all evident when I was there. Maybe its human nature to remember the good times and forget the bad.

In 1970 the campus was a beautiful private school perched on a hill with Georgian-style buildings mixed with an old classic mansion and quad. In fact, the campus seemed to be improving and expectations where high. My professors and courses there were excellent with reasonable class sizes. Instructors were smart and demanding, with 80% holding PhD’s in their fields.

How Did it Die?

There were lots of reasons for its downfall. Unfortunately, East Orange suffered from the migration out of the cities after the Newark riots of the late 1960’s. A substantial decrease in enrollment occurred. Enrollment peaked in the 1950’s around 2,000. But, even at 1,600 in 1969 it seemed to be thriving only to fall below 500 by the 1990’s.

A neglect of maintenance at the school began to match the deteriorating neighbor around it. And with an increase in competition from other colleges, It lost its ability to draw quality students. This led to an almost open admissions policy which drew more minorities and foreign students, many of which were unprepared and needed financial aid. But financial aid and student loans could only be sustained if enrollment was large enough to pay its operating expenses and debt payments.

Ironically, to add to their financial woes, the college was granted a 245-acre tract of land in Wantage, (Sussex County, NJ) by a benefactor, Wallace Wirths, to be used as a new campus site. After rejecting the idea of moving its entire operation to Wantage, it opened as a new small satellite campus, with all its expense and logistics, only adding to its operational woes.

Upsala continued to operate for years in debt, although being a private school it had no obligation to report that to the public. However, it did have to report to the Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools for accreditation, which began to warn of problems by the late 1980’s. By 1994, that organization threatened to take away their accreditation due to its ongoing financial problems unless the college came up with a workable plan.

There were efforts along the way to save the college near its end with negotiations, merger discussions with other schools and protests. 200 faculty and staff jobs were at stake. Sports programs were dropped. The school even promised that they had turned the corner.

But, by the time the student body and faculty understood the depth of the problem it was too late. A $12.5 million debt with a school facing a projected enrollment of about 500 could not work, even if costs could be cut dramatically and additional funds could be found to keep it temporarily afloat. It’s time had passed.

May 31, 1995, was the last day of operation for the school. The Trustees had hired an interim president to handle the sticky closing details as the college went into bankruptcy. All offices offices and classrooms were shut and emptied and all the that could be sold would go to the highest bidder – unless it would be later ransacked, as much of it was.

Even the entire satellite 245-acre Wantage campus was liquidated by selling it back to its benefactor’s family, the Wirths family, adding a mere $75,000 to the bankruptcy proceeds.

At The Final Commencement

Only one city official, Councilwoman Carolyn Meacham, attended the final graduation of the last 200 seniors. Here’s a summary of the mood of the day and a feeling of what would follow:

“It was like a funeral. What happened in Upsala is a travesty… Things should have been done to circumvent the process of closing. It’s not only affecting the people who went to the school and worked there but the closing is affecting the residents of the area.”

…once it closes down, vandalism is going to take place.”

Carolyn Meacham, East Orange Councilwoman (May 14, 1995)

A Campus Resurrected

The abandoned campus became a blight on the once prestigious neighborhood. The East Orange school board bought the entire campus for $4 million as Upsala was liquidated. It then split the campus in half with a plan to consolidate all its high schools into the “East Orange Campus High School” and sell the west half to the town for $1, with the hope of redeveloping it. The east retained some of the beautiful but tattered buildings like Puder, Beck and Viking Memorial Halls and connected them together with new construction in the style of the original campus. Today, the east campus still looks like a small college campus.

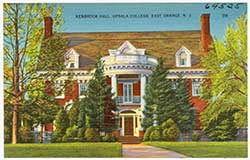

The 20-acre west campus was originally marked for upscale residential development. However, it languished for years and became a blighted and crime-ridden area even though it was the responsibility of the city to manage. West campus buildings became dilapidated. The old 1900 Charles Hathaway mansion (aka Kenbrook Hall), administration offices, dorms, chapel and library were demolished.

The city sold the west campus to a developer for $1.5 million to build upper-income residential houses in a semi-private enclave. Today, on the west side of Prospect Avenue at least, there is no trace of a once thriving college, just a $17 million, fenced-in community of 48 homes and 16 townhouses called “Woodlands at Upsala.”

a development – “Woodlands at Upsala”

<- West Campus | East Campus – >

Epilogue

Besides the unfortunate place and time Upsala found itself in, there’s a substantial argument that mismanagement and bad business decisions led to its demise. Maybe, it was an impossible situation as revenues declined, competition grew and costs for salaries, maintenance, improvements and security increased.

Today, the problems of private colleges and universities have not gone away and many have closed their doors too. Who knows if Upsala could have continued successfully if it was bailed out in its worse condition? If a comparison can be made to neighboring Bloomfield college, it would seem that its days were numbered as Bloomfield College was recently was absorbed into Montclair University as a satellite campus. And, there’s signs of enrollment and revenue declines at other trouble New Jersey colleges and universities.

In a recent article in the New York Times “A Private Liberal Arts College is Drowning in Debt, Should Alabama Rescue It”, a small private college that nearly fits the same profile as Upsala, has many of the same problems. Its financial woes have laid it low as it looks to state funds to rescue it lest it close and abandon its campus.

Perhaps the model of a small liberal arts college belongs to the past. As the expense of education has risen dramatically and students and parents are questioning the value of higher education and are seeking majors in new careers. But cities do come back. And, colleges may need to reinvent themselves too.

There’s at least a couple lessons to learn here. No educational institution is immune to the forces of the market and the incompetency of its leaders – regardless of its lofty goals. And, perhaps things could have been different if the college had followed its own motto, “Vincit omnia veritas.” Truth conquers all.

Sources

- Swedes And Deeds: The Ups And Downs Of Upsala College; Schaad, Jacob, Jr.; {Meadville, PA: Christian Faith Publishing, Inc., 2021

- Upsala photographs on Flickr.com

- Another defunct college campus, cleft in two. American Dirt, October 13, 2016

- Swedish Immigration Research Center, Augustana College, Rock Island, Il, database of online documents and images from Upsala’s history.

- One of N.J.’s oldest colleges may shut down. Here’s how things fell apart. NJ.com, October 24, 1921

- Various articles from Star-Ledger, Newark NJ – referenced from online access to NewsBank‘s Star-Ledger archive via Morris County Library system. Period reviewed Jan 1970 to Dec 2023. Probably the most comprehensive source of public information on the various problems and issues of Upsala.

- Various articles from New York Times, New York, NY – referenced from access to Timesmachine‘s New York Times archival system. Period reviewed Jan 1970 to Dec 2023.

- Against Odds, Revival For Troubled College; Mervyn Rothstein, New York Times, September 21, 1992, p 24

- A Private Liberal Arts College is Drowning in Debt, Should Alabama Rescue It, New York Times, Emily Cochrane December 23, 2023

- East Orange Public Library – maintains some school records, yearbooks and documents from Upsala College in its research section.

- Felician University – Holds transcript records for Upsala College. Requests can be made there for personal transcripts.

- Wikipedia – “Upsala” – a good summary of the history of Upsala College.